When Joanna lost her teenage son in a car crash just days before his high school graduation, her world collapsed.

He wasn’t just her child. He was her hope for a better future, her joy, her daily companion.

The grief that followed could not be explained away or contained by comforting clichés.

She struggled not only with the emotional devastation but also with the social expectations to “get back to normal,” the sudden loneliness in her home, the economic strain of funeral expenses, and the shifting role she had once confidently held as a mother.

Grief, as she painfully learned, is never a one-size-fits-all experience.

It is deeply shaped by who has been lost, when the loss occurred, and how it happened.

It also extends far beyond physical death, loss can emerge from divorce, trauma, unemployment, displacement, or even a broken reputation.

Grieving is a multifaceted process that affects every dimension of life. Dr. Pauline Boss, a pioneer in grief research, reminds us that “ambiguous loss” is as real as physical death, losses where closure is impossible still impact us emotionally, spiritually, economically, and relationally.

The death of a spouse, for instance, might mean not just sorrow but also lost income, companionship, sexual intimacy, and a sense of identity.

When a business collapses, it’s not just the revenue that vanishes, it’s the owner’s dreams, dignity, and structure of daily purpose. Grief, then, is not merely shedding tears.

It is finding meaning in the aching void left behind.

And too often, that struggle is misunderstood or prematurely dismissed by those around us.

Well-meaning friends and relatives may say things intended to comfort but that instead deepen the pain.

“You can always have another child,” said to a grieving mother, discounts the irreplaceable uniqueness of the one who was lost.

“I know exactly how you feel. When my dad died…” may shift the focus away from the mourner’s experience to the speaker’s own.

Even religious clichés like “We Christians don’t mourn like those who have no hope” can spiritualize away sorrow in an effort to appear faithful.

Yet, as researcher Dr. Kenneth Doka explains, these responses invalidate the mourner’s emotions, introducing guilt and isolation when what is most needed is presence, permission to feel, and space to lament.

What mourners truly need is not advice but accompaniment. Research by Dr. Alan Wolfelt, a grief educator, emphasizes that “being with” is more healing than “doing for.”

Quiet acts of service, bringing a warm meal, offering to clean, simply sitting nearby in silence, can minister more powerfully than any spoken words.

Often the greatest gift is just showing up. We are called not to fix the brokenness but to hold space for it, trusting that our compassion can become a bridge toward healing.

This is where faith intersects with care.

The ministry of presence mirrors the very heart of God, who promises, “I am with you always” (Matthew 28:20), even in the valley of the shadow.

Religious beliefs and cultural rituals, when engaged authentically, can ease the burden of grief.

While Western cultures tend toward a model of disenfranchised mourning, where individuals are expected to “move on” quickly and quietly, this often results in suppressed grief and prolonged suffering.

Disenfranchised grief, grief denied or delayed, can deepen into complicated grief, and when left unaddressed, may turn pathological.

Its toll is not only emotional but physical, weakening the immune system and manifesting as depression, anxiety, loss of appetite, heart attack, insomnia, numbness, or even panic attacks.

Yet even within these systems, faith can provide structure and hope, offering rituals like liturgies, memorials, and scripture readings that mark loss with dignity.

In contrast, African, Afro-Caribbean, and African American communities often model more communal expressions of grief, through wakes, family gatherings, days of remembrance, festive celebrations, and shared meals.

These expressions do not deny pain; they wrap it in the embrace of collective support, affirming the worth of the deceased and the importance of shared sorrow.

Grief is not a problem to be solved. It is a sacred journey that demands patience, presence, and grace.

When we recognize its complexity, emotional, spiritual, economic, and social, we are better equipped to walk alongside others who suffer.

As Pastor with decades of ministry and current doctoral work in grief and trauma psychology, I have learned that no scripture, no theology, and no cultural framework should ever rush a mourner through their valley.

Instead, let us weep with those who weep, honor every loss with dignity, and affirm through our faith that even in sorrow, love remains.

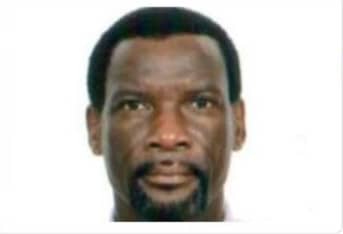

Pastor Stanton Adams is a seasoned minister with over 36 years of pastoral experience, currently serving as the Family Ministries Director for the South Leeward Conference.

He is deeply committed to helping families grow stronger in love, rooted in Scripture, and responsive to the realities of modern life.

Pastor Adams is also pursuing a doctorate in grief and trauma psychology, bringing both scholarly insight and heartfelt compassion to his ministry.

His work blends theological depth with practical care, offering hope and healing to those navigating life’s most challenging moments.